Authors

Onesmus Muchemi, Technical Officer – Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) Kenya

Martin Eyinda, Technical Officer – Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) Kenya

Rael Mutai, Regional Technical Advisor- Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) Kenya

Charles Ameh, Professor Global Health, Head Emergency Obstetric and Quality of Care Unit, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) United Kingdom

Introduction

The first Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths (CEMD, 2017) report in Kenya identified that sub-optimal care contributed to 92.4% of maternal deaths and made various recommendations for improved maternal and newborn health outcomes. Optimal antenatal care has a positive effect on both maternal and perinatal health. With funding from Takeda’s Global CSR Program through the Global Fund, the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) is supporting Kenya’s Ministry of Health in implementing strategies to improve antenatal and postnatal care in Garissa, Uasin Gishu and Vihiga Counties. The interventions include building the capacity of health care workers providing antenatal and postnatal services, standards-based audits (StBA) for quality improvement, onsite mentorship, and provision of basic equipment.

Quality improvement (QI) is the process of using appropriate methodologies and quality management tools to close the gap between current and desired performance levels. Good quality care requires the appropriate use of effective clinical and non-clinical interventions, strengthened health infrastructure, optimum skills, and a positive attitude of health providers.

Implementation of Standards-Based Audits (StBA)

The initial phase involves creating awareness of how the current practice is hindering the quality of care. Healthcare workers (HCWs) naturally resist change. Updating their knowledge and skills on antenatal and postnatal care (ANC & PNC) and StBA, coupled with mentorship, works well in making them aware of the gaps in their current practice.

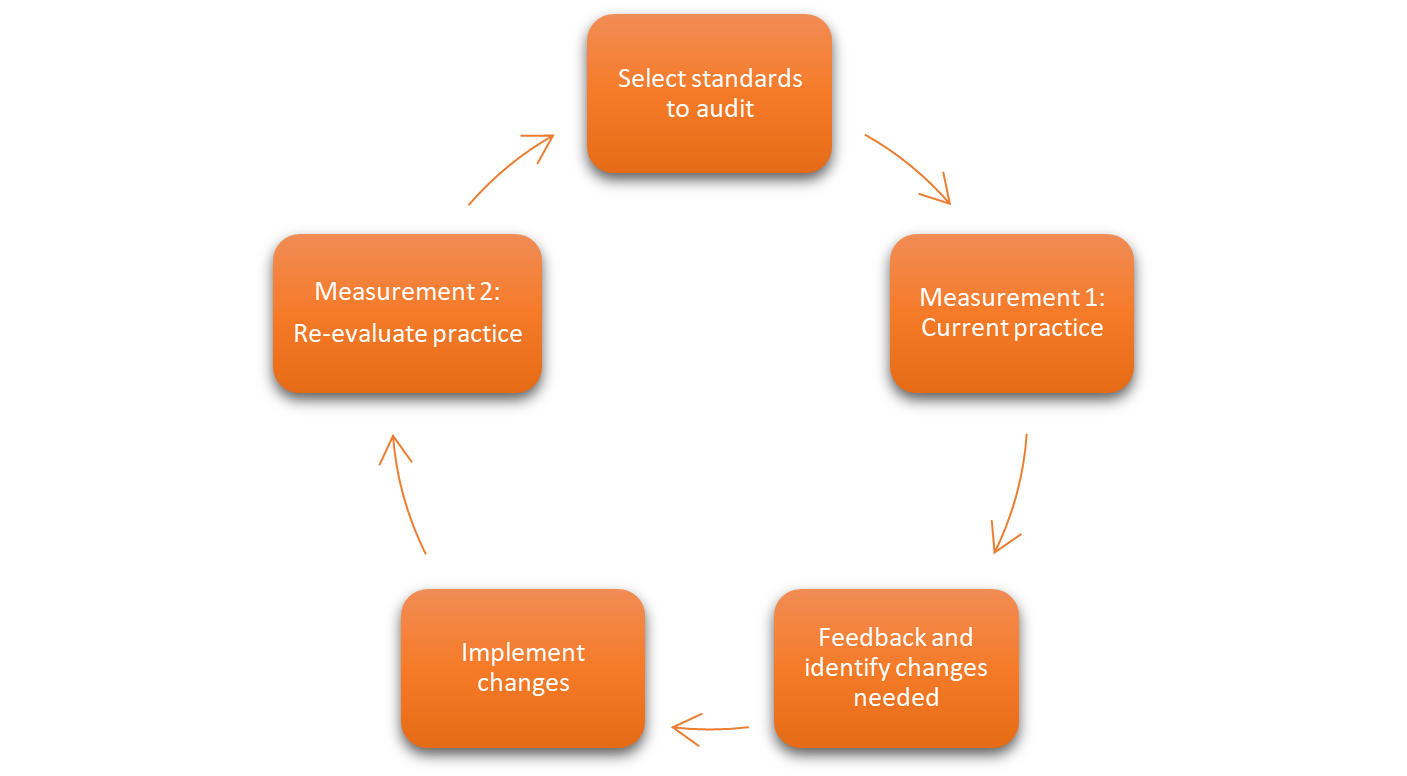

In StBA, the current practice is carefully examined through a baseline assessment (Measurement 1) against a selected standard. As a result, the HCWs become aware of the current practice and the gaps. The trainers, the mentors, and the QI champions play a crucial role at this stage. The better the need for change is felt, the more HCWs feel the necessity, urgency, and motivation to adopt change. This works better if the same healthcare provider is trained in both the ANC & PNC course and the StBA methodology.

The next phase entails introducing the changes while prioritising them to reflect local realities. At this stage, the HCWs often encounter uncertainty, fear, feelings of being incapable, and a sense of increasing workload. This can potentially be worsened by a lack of essential equipment and supplies, a lack of support by managers, a shortage of staff and a lack of supportive mentorship and follow-up. A collaborative approach among the Quality Improvement Team (QIT) members to implement the changes supports ownership, including rewarding quick wins associated with the change. Provision of resources, support from management, mentorship and support supervision are necessary ingredients for change.

In partnership with the County Health Management Team (CHMT), LSTM supplements the gaps in essential equipment, supports periodic facility visits, tracks mentorship, and the progress on implementation of StBA and other QI activities.

The final step of the StBA cycle includes sustaining the new change. This is the difficult part, and yet it is the most important. There is the risk of falling into the old behaviour. The process should be introduced carefully right from the initiation phase. Acknowledging efforts positively reinforces the new behaviour. Similarly, establishing systems and processes, promoting a culture of quality, allocating budget and resources, and embedding the change into the annual operational plans and policies are essential. In this regard, LSTM, in collaboration with the CHMT, supports Knowledge Management and Learning (KML) events in which stakeholders exchange ideas on best practices and ways to sustain positive changes and track the implementation of action plans developed during KML events.

The Sustained Changes

Following the training of HCWs on ANC & PNC, and StBA in QI from February 2022, all project facilities have embraced new knowledge and skills. As a result, new practices have emerged, and service delivery improved:

- Respectful maternity care has become a norm in most facilities. Staff have changed the way they viewed and treated clients previously. The donated screens have improved privacy/confidentiality during client examinations.

- The quality of postnatal care has improved. Previously, it was just a postnatal check-up and nothing more was done. Garissa County Referral Hospital, for example, has equipped the postnatal clinic with oxygen, a nebulizer, and a suction machine. The nurse-midwives are enabled to conduct neonatal resuscitation at the clinic before the baby's admission. Neonates with complications are now admitted directly from the postnatal clinic to the ward, not from the emergency department.

- Health messages have been intensified. For instance, in Garissa County Referral Hospital, health messages are delivered every morning. Previously, this was done either once a week or not at all.

- Performance of some services has been initiated or improved in most facilities. In Iftin Sub-County Hospital, random blood sugar and Hepatitis B screening was not performed previously. Screening for urine and haemoglobin was done if the client complained or if there were signs and symptoms. Screening for HIV and Syphilis has improved.

- Mental health and Gender-Based Violence (GBV) screening was not done previously. This is now being done and recorded on the mother-child booklet (MCH) and the register.

“Since training, we have diagnosed two cases of depression in our facility using the screening tools. One was a mother with suicidal thoughts who was six weeks pregnant, and the other was a mother with a two-month-old baby who expressed feelings of wanting to harm herself and the baby. We referred the two mothers to the psychologist for counselling and treatment.”

Nurse-midwife, Garissa County Referral Hospital

Conclusion

Equipping healthcare workers in selected facilities in Garissa County with knowledge and skills on ANC & PNC and standards-based audits has made them more proactive in addressing gaps in quality of care and innovative in solving problems affecting their health facilities. However, to drive the process, take it to scale, and institutionalise it, administrative and managerial support is necessary to overcome barriers in the change process.