The Emergency Obstetric Care and Quality of Care unit has implemented mentoring to complement short multidisciplinary competency based hands-on training for skilled health personnel in LMICs since 2009. This strategy is to ensure retention of knowledge and skills after competency-based training. Our mentoring intervention package has been/is been implemented in the FCDO multi-country Making it Happen programme (2009-2016), FCDO Kenya, Reducing Maternal and Newborn Deaths Programme(2014-2023),UNFPA ACCESS programme (2020-2021), and Takeda pharmaceutical/Global Fund Quality Improvement of Integrated HIV, TB and Malaria Services in Antenatal and Postnatal Care Programme (2020-2023).

What is mentorship?

Mentorship has been defined as a relationship in which a more experienced or more knowledgeable person helps to guide a less experienced or less knowledgeable person. It is a learning and developmental partnership between someone with greater experience and someone who wants to learn. (1) The mentor may be older or younger than the person being mentored, but he or she must have developed a certain area of experience and expertise beyond that of the mentee.

Clinical mentorship serves as an essential sequel to both pre- and in-service training, where the mentoring encounters result in re-enforcement of skills and behaviours learned in training.

A broader definition of mentorship includes aspects of support beyond improvement in clinical skills and service delivery to encompass career guidance and development of life-skills, but the focus of this training course is on clinical mentorship as applied to the workplace.

In maternal and newborn (MNH) context a mentor is someone/clinician with substantial expertise in MNH who can provide ongoing mentoring to less-experienced MNH providers by responding to questions, providing feedback, and assisting in management of maternal and newborn conditions.

Where are mentors based?

Mentors may be locally based or may travel for face-to-face mentorship encounters, with telephone or internet contact to supplement interactions between visits. However, there are benefits to facility-based mentorship, where mentors and mentees can work alongside each other in clinical areas on a frequent basis. Side-by-side working enables mentorship opportunities as extensions of shared activities, for example, ward rounds, theatre sessions and clinics. It is essential for mentors to have sufficient time to observe their mentees and discuss practice and agree a plan of action to improve practice. Tools such as checklists may be used by mentors for objective assessment of mentees concerning the desired sequence of steps in providing specific care. Mentees should also keep a log of key procedures, difficulties encountered or issues to clarify when they meet their mentors. Facility based simulation-based training (low-dose high frequency training) can be organised by facility-based mentors to address knowledge and skills deficits observed amongst mentees. (2,3) The progress in working towards quality improvement targets can be closely monitored and supported by facility-based mentors.

What skills do mentors require?

The mentor must possess appropriate skills and experience around clinical work in question. Mentors require the ability to listen to the mentee to understand the areas where they feel in need of further support, but also to see for themselves any areas of weakness where the mentee needs support to foster improvement because of on-the-job observation. The mentor should have well-developed and flexible teaching skills but, beyond that, generic mentoring skills to facilitate the mentee in reflecting on their performance. The mentor should both give feedback and encourage self-generated feedback. As a part of the mentoring process, setting mutually agreed targets with timelines can be helpful to aid development, if reflection upon targets achieved or missed is viewed through a supportive rather than a judgmental lens, with the aim of aiding the mentee as they work to overcome obstacles.

The relationship requires dual reflection, with the mentee reflecting on the lessons emanating from the mentorship encounter, but equally, the mentor reflecting upon encounters with their mentees. They themselves benefit from having a relationship with a lead mentor, with whom they can reflect on their mentorship encounters.

What is the role of Supportive supervision?

Supervision has been used by mid-level managers to help staff improve their own work performance. Traditionally, supervision is provided by district level managers through periodic visits to health facilities using checklists. Typically, the approach may slip from one of helping staff to improve to a focus on finding faults with individuals, irregular problem-solving by supervisors, little or no follow-up and high prevalence of punitive actions (control focused supervision). Ideally, supportive supervision is a process of helping staff to improve their work performance continuously and it is characterized but open, two-way communication, building team approaches that facilitate problem solving. It also focuses on monitoring performance towards goals and using data for decision making. It depends on regular follow-up with staff to ensure that new tasks are being implemented correctly. (4) This approach has been reported to be successful for community health workers and in immunization programmes but availability of resources may limit the ideal implementation of supportive supervision. (4,5) For example, too few district level supervisors and insufficient resources to support regular travel to health facilities may create the perfect scenario for ‘control’ focused supervision.

In reproductive/maternal health, there is evidence of the effective use of district level supervisors to support facility-based mentors. (6)

Mentoring training package

We use evidence-based learning and teaching methods suitable for adult learning and which have been shown to result in improved communication, and improved evidence-based practice. Our 2-3-day training course delivers teaching and interactive discussions (80% practical/simulation/hands-on, 20% short lectures) regarding the mentorship process and techniques for good mentorship together with scenarios to practice mentorship encounters with the aim of developing mentorship competencies for clinical mentors. To ensure sustainability and continuity we support Ministry of Health to adapt existing mentoring package based on this evidence-based approach. The training is complemented by a manual, that contains various tools.

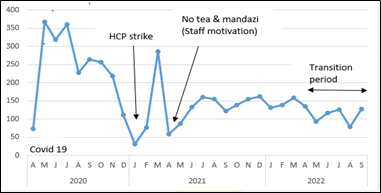

Under Emergency Obstetric Care and Newborn Care programmes, mentors are equipped with checklists for Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care skills procedures and templates for developing low-dose high frequency training sessions to address gaps in knowledge and skills observed amongst mentees. During the covid 19 outbreak, facility-based mentors were supported virtually by EmOC&QoC unit technical team. Group and one-to-one mentoring sessions were organized regularly in supported health facilities, organized and lead by trained facility-based mentors.

Under the Takeda Pharmaceutical/Global Fund Quality Improvement of Integrated HIV, TB and Malaria Services in Antenatal and Postnatal Care Programme, the package has been adapted and includes the following components:

- supporting the application of workshop learning on ANC, PNC, and QI to clinical area

- maintaining and progressively improving the quality of MNH at health facility level

- building the capacity of first- and second-level providers to manage unfamiliar or complicated maternal and newborn cases referring them when appropriate; and

- improving the motivation of health care workers by providing effective technical support.

Implementation of a 3-day intensive training programme will commence in 2022. Find out more about our work with Takeda.

References

1. SCOPME. An enquiry into mentoring: supporting doctors and dentists at work - Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical Education in England - Google Books [Internet]. Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical Education in England. London; 1998 [cited 2020 Nov 11]. Available from: https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/An_enquiry_into_mentoring.html?id...

2. Willcox M, Harrison H, Asiedu A, Nelson A, Gomez P, LeFevre A. Incremental cost and cost-effectiveness of low-dose, high-frequency training in basic emergency obstetric and newborn care as compared to status quo: part of a cluster-randomized training intervention evaluation in Ghana. Global Health [Internet]. 2017 Dec 6 [cited 2019 Aug 14];13(1):88. Available from: https://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12992...

3. Atukunda IT, Conecker GA. Effect of a low-dose, high-frequency training approach on stillbirths and early neonatal deaths: a before-and-after study in 12 districts of Uganda. Lancet Glob Heal [Internet]. 2017 Apr 1 [cited 2020 Nov 11];5: S12. Available from: www.thelancet.com/lancetgh

4. World Health Organization. Training for mid-level managers (MLM) Module 4: Supportive supervision [Internet]. Geneva; 2008 [cited 2020 Nov 11]. Available from: www.who.int/vaccines-documents/

5. Singh D, Negin J, Orach CG, Cumming R. Supportive supervision for volunteers to deliver reproductive health education: a cluster randomized trial. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2016 Oct 3 [cited 2020 Nov 11];13(1):1–10. Available from: http://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s1...

6. Ndwiga C, Abuya T, Mutemwa R, Kimani JK, Colombini M, Mayhew S, et al. Exploring experiences in peer mentoring as a strategy for capacity building in sexual reproductive health and HIV service integration in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2014 Mar 1 [cited 2020 Nov 11]; 14:98. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3942326/?report=abstract