Authors

Onesmus Muchemi, Technical Officer – Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) Kenya

Martin Eyinda, Technical Officer – Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) Kenya

Irene Nyaoke, Senior Technical Officer - Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) Kenya

Rael Mutai, Regional Technical Advisor- Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) Kenya

Charles Ameh, Professor Global Health, Head Emergency Obstetric and Quality of Care Unit, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) United Kingdom

The case for blended learning

Healthcare providers play a crucial role in implementing health interventions. However, in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), they often lack the necessary knowledge and skills to deliver high-quality care. The 2019 Kenya Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths (CEMD) revealed that enhancing the care for 88.1% of the women who died could have led to better outcomes. One of the main recommendations was to focus on building capacity, which includes providing mentorship to healthcare providers.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, there has been a growing trend in using blended learning to educate healthcare workers. Blended learning is the organic integration of thoughtfully selected and complementary face-to-face and online approaches and technologies. Since 2021, with funding from Takeda’s Global CSR program through the Global Fund, the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) has been partnering with Kenya’s Ministry of Health (MOH) to deliver a project aimed at improving the quality of integrated HIV, TB, and Malaria services in antenatal and postnatal care (ANC-PNC). One of the key programme outputs has been strengthening the capacities of health workers in Garissa, Vihiga and Uasin Gishu counties to scale up best practices in ANC-PNC for improved maternal and newborn health outcomes. LSTM has adopted blended learning as an approach to strengthening the capacity of healthcare workers. This is in addition to the traditional face-to-face learning.

Garissa County has 328 nurse-midwives who provide maternal and newborn health services. Among them, 150 work in the main referral hospital, 66 in the seven sub-county hospitals, and 112 in health centres or dispensaries. Nurse-midwives make up most of the health care providers for maternal and newborn health services, in addition to medical doctors and clinical officers. Garissa is a large and arid county with dispersed health facilities, presenting challenges in transportation and communication due to difficult terrain and security concerns. Heavy rains often cause flooding, complicating travel and increasing costs. Consequently, most health care worker training occurs in the main town centre, Garissa. For these reasons, face-to-face training in Garissa is more expensive than in the other two project counties. A blended antenatal and postnatal care (ANC-PNC) course was recently held in Garissa County.

The training process

The blended ANC-PNC course consisted of three phases: self-directed learning (SDL) lasting two weeks, real-time online learning on Zoom taking three days (2.5 hours per day), and the final two-day face-to-face workshop in Garissa town. LSTM partnered with the World Continuing Education Alliance (WCEA), an e-learning platform, to administer the SDL.

The course content focused on evidence-based screening, therapeutic interventions, and health promotion during and after pregnancy to meet the physical, mental, and social aspects of maternal and newborn health. It also covered essential components of care, including integration of HIV, TB, and malaria services, as well as respectful maternity care, communication, and emotional and mental health assessment. The course content was delivered as a pre-test, brief notes, videos, and a final post-test. A completion certificate and CPD points were awarded to those who completed and passed the course.

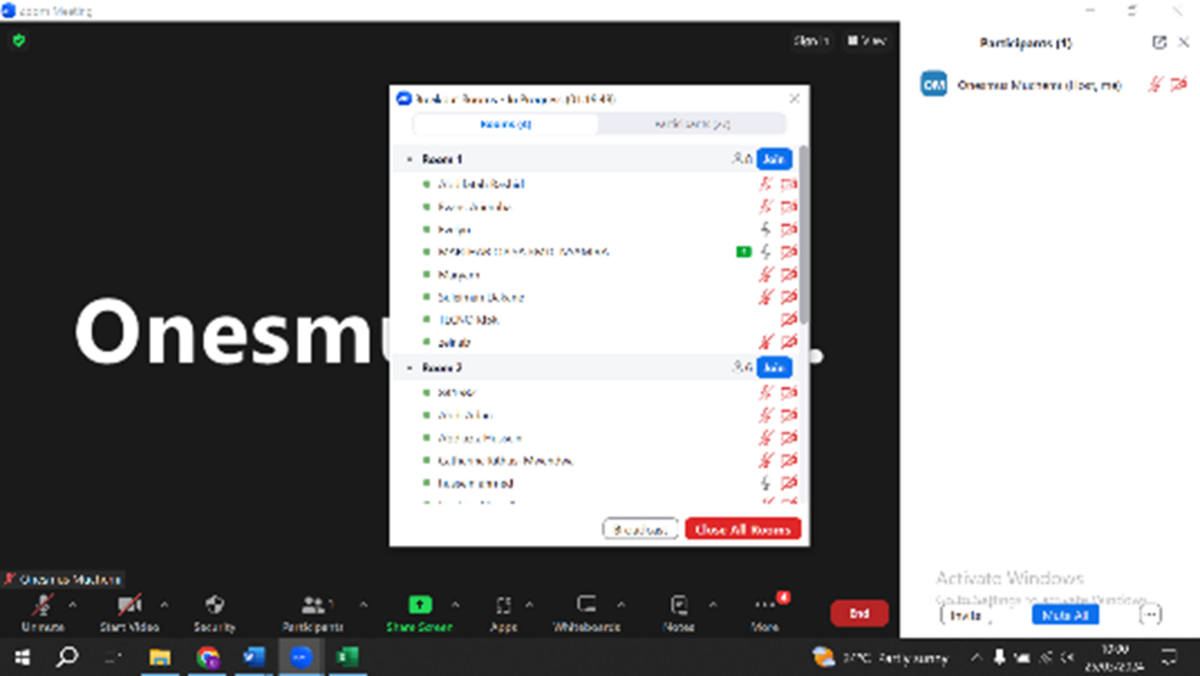

Participants were provided with internet bundles to undertake the online Zoom course. Eight trainers facilitated the course, including one obstetrician and seven midwives. Four breakout rooms were created to support the group discussions, each facilitated by two trainers. All sessions were discussions guided by prepared case scenarios. Of the 38 participants, 30 (79%) completed the Zoom course.

The face-to-face course preparations included auditing the training equipment and preparing breakout rooms for the skills pre-test planned for the first day. The course content was delivered through group discussions, role-play, practical skills sessions, scenarios, presentations on flip charts, plenary discussions, and a recap. The course ended with participants performing a knowledge and skills post-test.

Participant Feedback

When asked to give feedback at the end of the course, participants argued that blended learning is more flexible than continuous face-to-face learning. The self-directed and online real-time (Zoom) courses allow them to learn in the comfort of their duty stations.

The materials on the WCEA platform are interactive, including the videos. Despite geographical distances, participants and trainers could share information during the self-directed course (through the WhatsApp groups) and the Zoom sessions. The face-to-face sessions allowed them to interact and practice the skills. They explained that they could update their skills and felt more confident about providing better-quality services after the training.

“As you advance in age, the ability to comprehend learning materials is low. Blended learning is a better method because it gives ample time, and you learn at your own pace. There is more time for learning when the different methods are used, such that if you do not understand using one method, you get clarity during the other sessions. With a full face-to-face course, time is often compressed, and everything must be completed within a scheduled time. There is often less time to interact and comprehend the content.” Nurse midwife, Korakora Health Centre

However, some participants experienced challenges during blended learning. Many participants used their mobile telephones to access the course. Internet fluctuations were encountered during the self-directed course and the Zoom sessions, which interrupted session continuity. Due to the shortage of healthcare workers in rural facilities, some staff attended Zoom sessions while still providing services. In addition, the WCEA App cannot be used offline, and participants cannot download materials so that they can study or refer to them on their own time. Participants feel that support and encouragement from facility managers are necessary during the learning sessions, and support with essential equipment will motivate them to practice what they have learned.

Conclusion

Support supervision is infrequent in under-resourced areas like Garissa County, and there is often a staff shortage. This can lead to a decline in health workers' knowledge and skills, resulting in poorer quality of services. Blended learning offers an alternative way to update health workers' knowledge and skills in antenatal care (ANC) and postnatal care (PNC). This method is flexible, causes minimal disruption to service delivery, and is cost-effective due to fewer workshop days.