Research led by Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM), highlights the need for antimicrobial stewardship to be targeted and research-led – if it is to be effective.

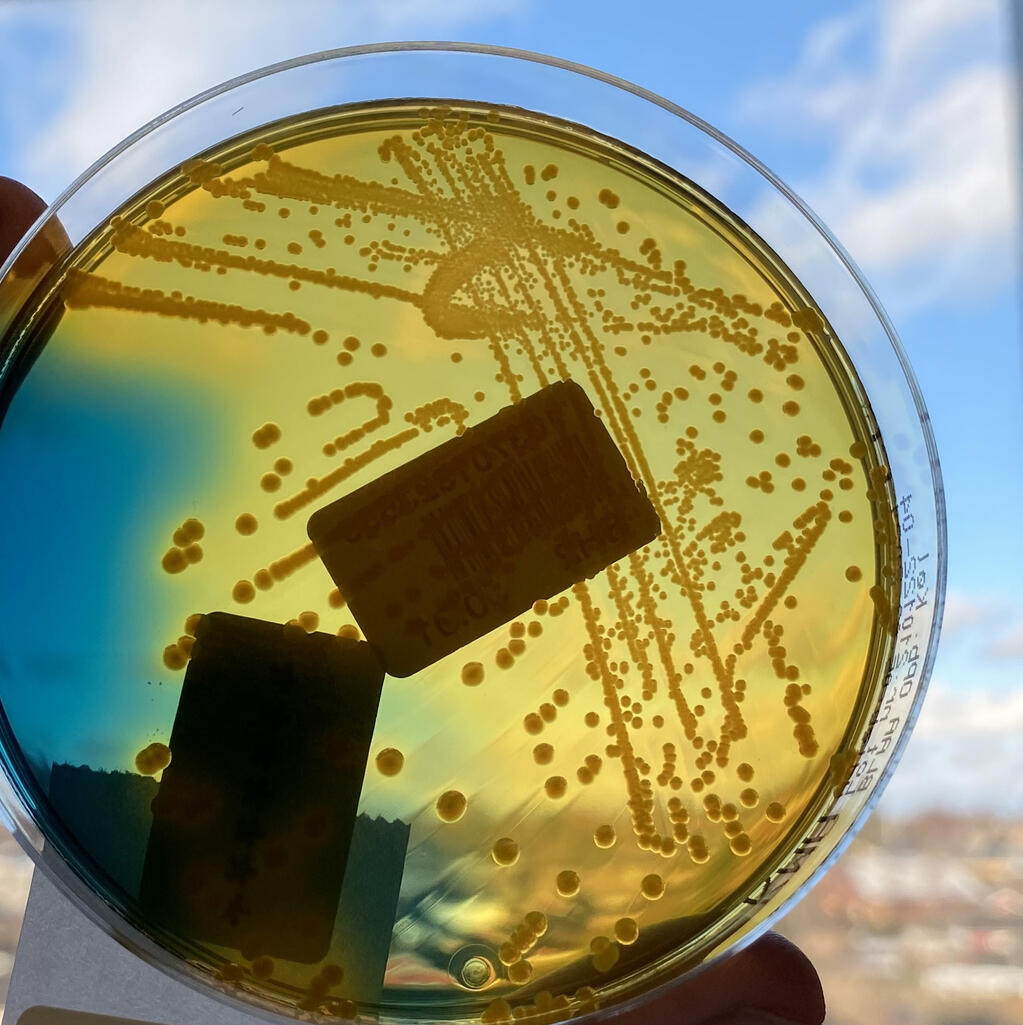

A study published in the Nature Microbiology journal, focused on drug-resistant bacteria, including E. coli, which produce extended-spectrum beta-lactamase enzymes (ESBL) that destroy antibiotics.

By sampling the stool of 425 adults in Blantyre, Malawi, over six months, the study team drew important conclusions about gut colonisation with ESBL bacteria, by examining the role that duration and type of antibiotic use had on carriage of drug resistant bacteria in the group.

Bacteria are experts at developing ways to evade or inactivate antibiotics. Antimicrobial stewardship is employed to support the best use of antibiotics. Shorter courses of antibiotics have been trialled to reduce antibiotic resistance, but the LSTM study found this produces limited results.

The LSTM study found even single doses of antibiotics can have a month-long effect in promoting carriage of resistant bacteria and that stopping antibiotics at two days, rather than seven, has very little effect. Joe Lewis, lead author of the study, and Honorary Clinical Lecturer at LSTM said: “We need to ensure we target antimicrobial stewardship to where it can make the most difference. Our study suggests that avoiding antibiotics altogether is much better than starting a course, stopping to wait for test results, then starting again. We need new rapid tests to achieve this safely.”

Antibiotic resistance is a major global problem that threatens many of the advances of modern medicine. Shorter courses of antimicrobials have been suggested to reduce selection pressure, which allows antibiotic-resistant bacteria to survive and multiply. However, the processes around selection are poorly understood and a reduction in overall use of antibiotics may be a better approach.

Many people genuinely need antibiotics urgently as Professor of Microbiology at LSTM, Nicholas Feasey, explains: “There are tests that indicate whether antibiotics are really needed but these often take two days or more to come back, and in people who are critically unwell (with suspected sepsis for example) we need to start antibiotics straight away.

Antimicrobial stewardship advocates reviewing and stopping antibiotics as test results come back, often at 48 hours, but our research shows colonisation with resistant bacteria could already have occurred by this point anyway, so stopping the antibiotic course could be delayed in these circumstances.”

Overall, the study’s findings support reducing antibiotic use where possible. This helps preserve antimicrobials for future generations, ensuring they remain available to people who need them for complex infections, where resistance to commonly used antibiotics is increasing. It’s hoped this targeted research, combined with the modelling and whole-genome sequencing seen in the study, can help support the development of policy around antimicrobial stewardship in Malawi.

Lewis, J.M., Mphasa, M., Banda, R. et al. Colonization dynamics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales in the gut of Malawian adults. Nat Microbiol (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-022-01216-7