The seminar series continued today with a presentation from LSTM’s Senior Lecturer Dr Mike Coleman. His talk entitled: Data to improve vector control programmes, was introduced by LSTM’s Director, Professor Janet Hemingway.

Dr Coleman began by explaining that data is essential to ensure that vector control programmes are successful, but the data help by such programmes is not always accessible and even if it is it is often help in silo. These silos may be further fragmented, sitting with a number of parties, NGOs, government departments or research institutions. This data may be recoded differently, not aggregated and not talking to each other.

It is for this reason that LSTM and partners designed the Disease Data Management System (DDMS), to assist in malaria and dengue control programmes with data integration and management. He explained that information upon which decisions are made needs to be accurate, timely and complete and talked through how the DDMS was able to add spatial data as well as allowing the programme to define terms, crucial in ensuring that data is captured in the same fields across different locations or provided by different organisations.

Using an example of vector control from Zambia, Dr Coleman talked about how, by looking at the problems spatially they were able to have a clearer idea of where the problem was. They could then link this to the entomological information and data relating to where and for how long different insecticides had been used. This information was key in bringing about policy change and the first country wide insecticide resistance management plan.

DDMS has since been adapted for new vector borne diseases, and he explained how his team had been working in the Indian state of Bihar, looking at visceral leishmaniasis (VL). The system was utilised to analyse the quality and coverage of the indoor residual spraying with DDT as well as resistance data, which was used to drive policy change. Now the state uses different pumps, imported by Dr Coleman’s group as well as pyrethroid insecticides, to which the sand fly vector currently has lower resistance.

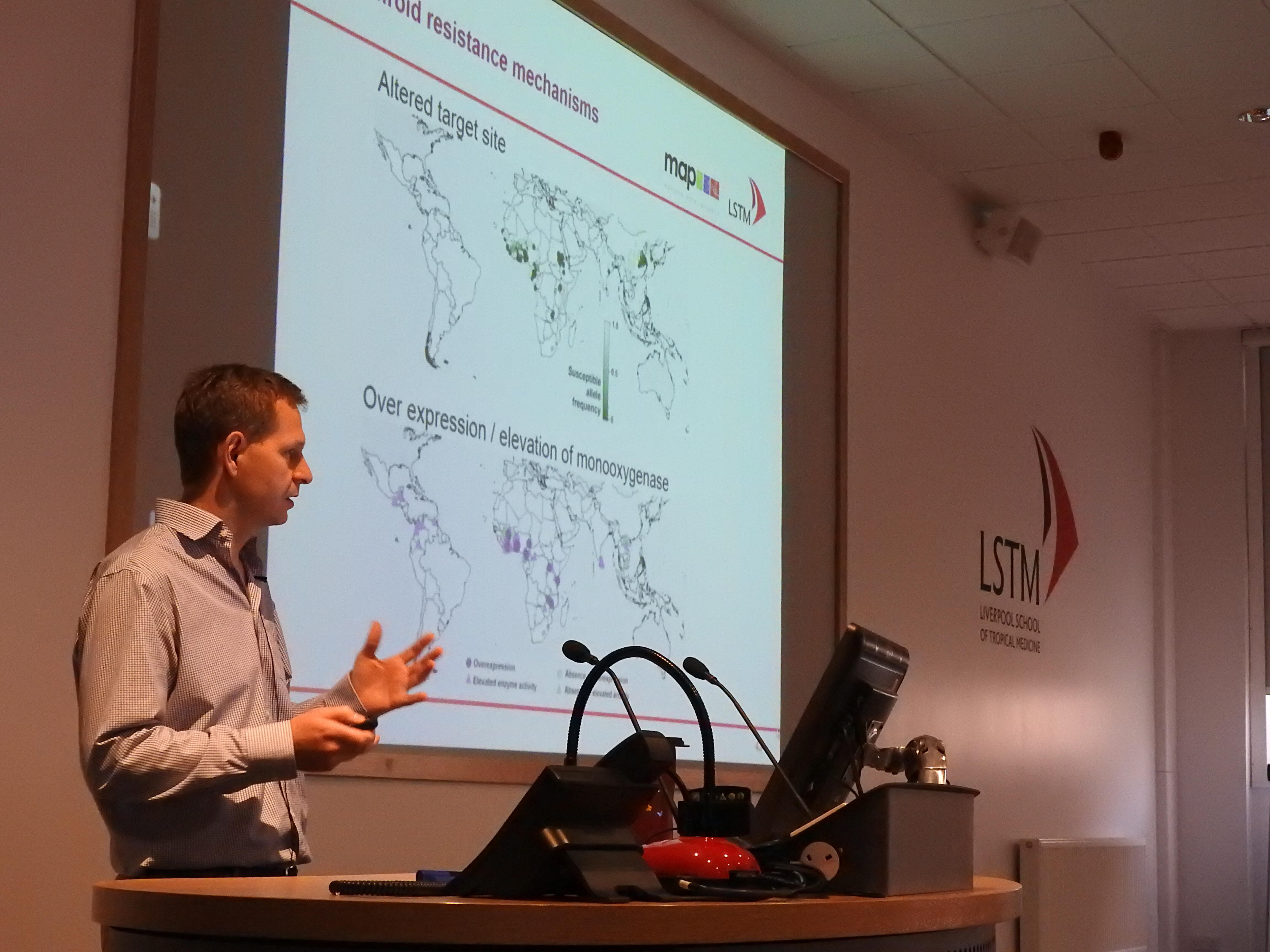

Dr Coleman concluded by talking about how their efforts are now expanding. His team are working with a group at the University of Oxford in the Malaria Atlas Project (MAP), identifying where the gaps in data are relating to resistance, so that maps can be produced that not only identify the current state of resistance but, investigating the drivers of selection of the genes responsible for resistance, predict how resistance may look in the future.

You can see the full lecture here.