LSTM’s Seminar Series continued with a presentation by Dr Nathan Ford entitled: Uses and limits of research evidence in shaping global HIV policy and practice, and was introduced by Dr Miriam Taegtmeyer, Senior Clinical Lecturer in the Department of International and Public Health at LSTM.

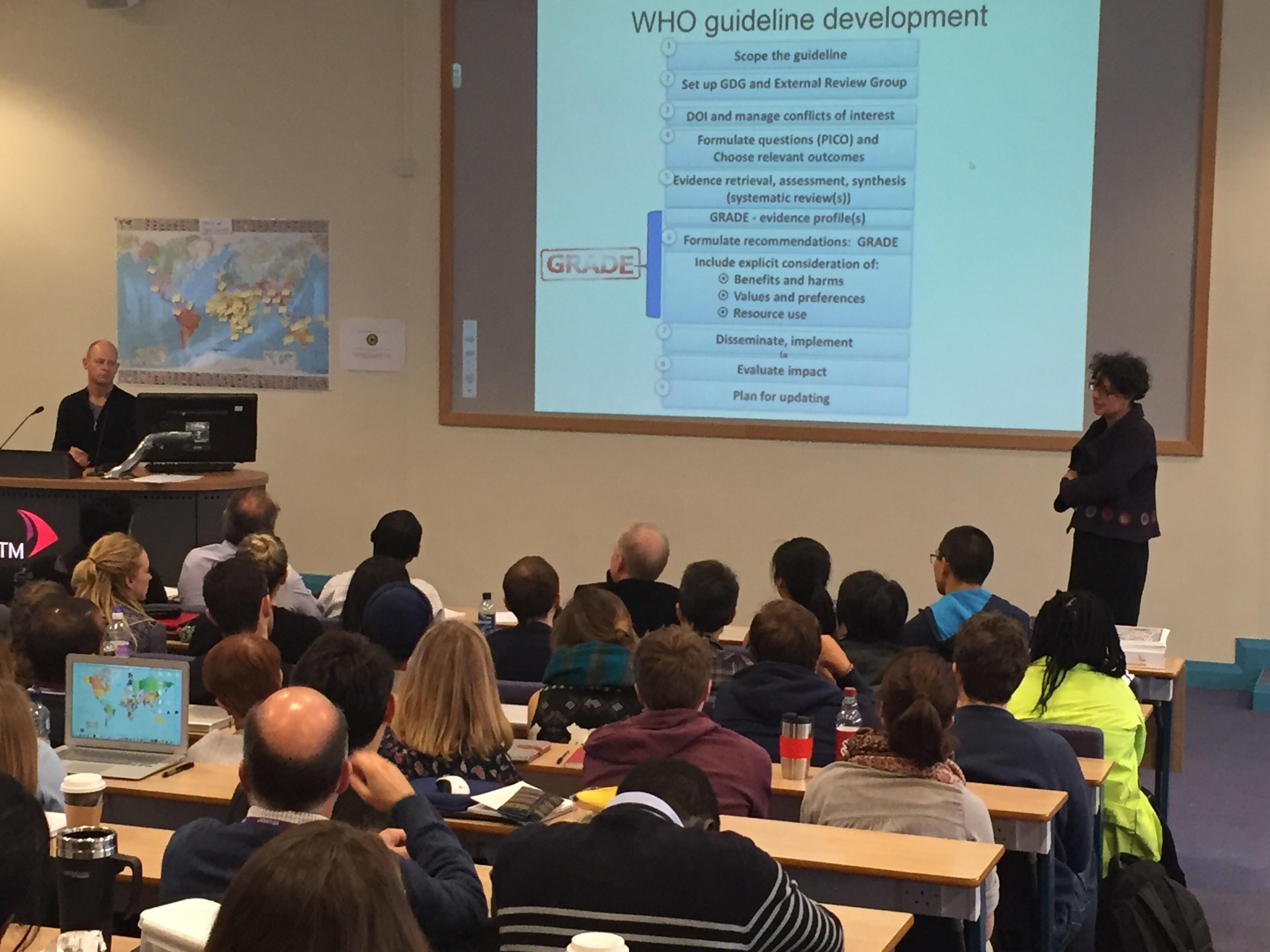

Dr Ford had a long standing career at Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) as Head of the Medical Unit in South Africa, and is now at the heart of the World Health Organization’s Department of HIV/AIDS and Global Hepatitis Programme, in Geneva, working as Programme Manager where he leads and contributes to guideline development and chairs the Guidelines Review Committee.

Dr Ford began his talk by saying that the criteria for designing a study should be to ask an important question and answer it reliably. In terms of collating evidence, he discussed the traditional research hierarchy spanning from case reports to meta-analysis, which will lead to policy development and practice change. He illustrated the gap between the acceptance of evidence and changes in policy and practice with the example of the 3 year delay by African countries to respond to changes in policy guidelines by the WHO for the treatment of severe malaria.

He went on to explain the numerous issues surrounding delays in practice change following the release of guidelines by WHO. Challenges include the feasibility of the new intervention, acceptability of it by the end-user and health provider, timing of the new intervention, applicability in all settings, cost as well as the importance of local and international politics. He explained each of these areas giving examples to demonstrate the challenges faced for HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART) and how some communities resolved these. In particular, an intervention in which a small group of community members work together, allowing a different member to attend clinic every month to pick up treatment for the whole group, reducing visits from every month to once in every six months.

Dr Ford also highlighted the fact that global policy change can happen in the absence of evidence, citing the example in Malawi where nurses were permitted to prescribe ART to patients, as there were far more nurses than doctors. This led to the change being adopted in a number of countries, the benefits only being shown afterwards.

Dr Ford summarised by saying that an intervention might be sound in theory but it will be useless if it can’t be taken to scale. He ended by suggesting ways we can ensure research informs policy, by asking important questions, asking those questions at the right time, answering them reliably and considering the issues in context of the need.