By Professor Russell Stothard, HUGS Lead Investigator

Research conducted by the HUGS (Hybridisation in urogenital schistosomiasis) team at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine has shown Male Genital Schistosomiasis (MGS), a debilitating and often overlooked disease, potentially affects over 40 million men in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

Despite its severe impact on men's health and its potential role in facilitating the spread of other infections, such as HIV, MGS has remained under the radar of global health initiatives. Research shows we desperately need a paradigm shift in public health policy to address this hidden crisis.

Since 2009, "urogenital schistosomiasis" (UGS) has been used to describe infections caused by the blood fluke Schistosoma haematobium. This parasite, transmitted by freshwater snails, is prevalent in many parts of SSA. While the female form of the disease, female genital schistosomiasis (FGS), has gained attention from researchers and public health officials due to its links with HIV transmission, MGS remains significantly under-investigated.

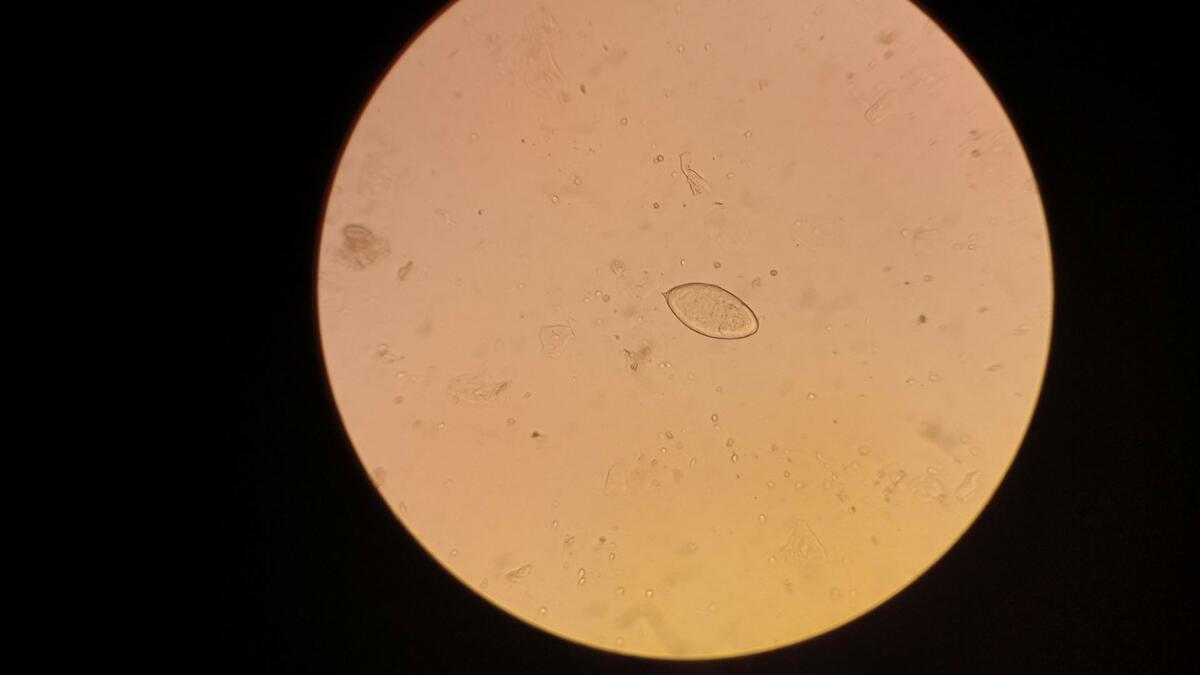

Our new study conducted using advanced real-time PCR diagnostics with fishermen along Lake Malawi found that 26.6% of men suffered from MGS. This figure starkly contrasts with the mere 10.4% detected through traditional microscopy, looking at semen samples through a microscope, highlighting the limitations of current diagnostic practices and the hidden extent of the disease.

This striking data suggests that millions of men across SSA could be affected by MGS, yet the disease is neither adequately diagnosed nor treated.

This is despite MGS having severe and life-changing consequences for those infected, the most common of which are disability and irreversible infertility. Common symptoms also include blood in urine and semen and pain during intercourse and while urinating. MGS can also be deadly. While this is rare, it still amounts to an estimated 11,792 deaths globally per year.

The burden of MGS remains unquantified. This lack of data translates into insufficient funding and resources for combating MGS, perpetuating a cycle of neglect.

Effective management of MGS requires a multi-faceted approach. First and foremost, there is an urgent need for better diagnostic techniques. Traditional methods, like microscopy of semen samples, are culturally challenging and often insufficient. Advanced diagnostics, such as real-time PCR, should be made more widely available to accurately identify and measure the disease's prevalence and severity.

Moreover, MGS should be integrated into existing public health frameworks. The disease's management should not be isolated but instead included in broader sexual and reproductive health programs, particularly those targeting HIV. Given the potential of MGS to facilitate HIV transmission, combined treatment and prevention efforts could yield significant public health benefits.

Another crucial aspect is the accessibility of treatment. Praziquantel, the primary drug used to treat schistosomiasis, should be readily available year-round. Regular and repeated treatment cycles might be necessary to manage symptoms and prevent reinfection, especially in high-risk communities.

Public health campaigns must also focus on raising awareness about MGS. Many affected men might not seek help due to a lack of knowledge about the disease and its symptoms. Educating communities about the importance of recognizing signs of MGS, such as blood in urine or semen, could lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment.

Lastly, there is a need for substantial investment in research. More studies are required to fully understand the epidemiology of MGS, its health impacts, and its interaction with other infections. Such research could provide the evidence base necessary to drive policy changes and allocate resources effectively.

The case for addressing MGS is clear. It is a prevalent and debilitating condition that has been neglected for too long. By investing in better diagnostics, integrating MGS into existing health programs, ensuring treatment accessibility, raising awareness, and fostering research, we can begin to bridge the gap in male genital schistosomiasis management. The time for action is now, and the health of millions of men across sub-Saharan Africa depends on it.