Ahmad Alcheikh. DTMH, September 2018

One of the great things about the DTM&H course is the exposure to laboratory aspects of tropical medicine. It’s cool to see the bugs responsible for many of the infectious diseases in all their microscopic glory. Here’s a selection of baddies I photographed in the Dagnall Lab at LSTM.

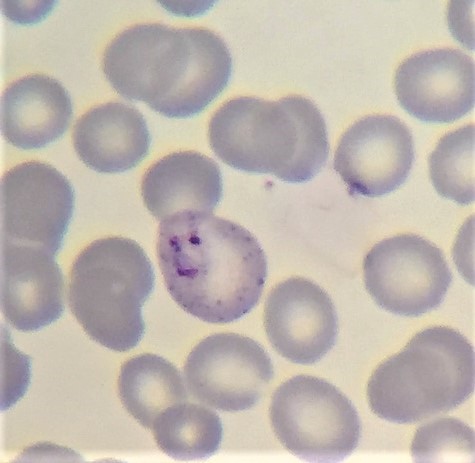

Giardia

This sad-looking little critter is a eukaryotic organism, which means its cells (all one of them) are more like ours than bacteria. It causes a diarrhoeal illness by growing in and invading the intestines. It was first observed all the way back in 1681 by Anton van Leeuwenhoek, a pioneer in microscopy, who examined a sample of his own diarrhoea under the microscope. Besides being gross, this little exercise revealed the agent responsible to be Giardia lamblia, which is said to look like a clown face, but I think it looks more like a cheeky ghost. The ‘eyes’ are actually two cell nuclei.

Giardia infects hundreds of millions of people worldwide, causes chronic diarrhoea and can cause malnutrition.

Hard tick

Hard ticks are ectoparasites, meaning they live outside of their ‘host’. Female hard ticks can be distinguished by the little ‘shields’ on their backs, as seen in the photo. She will feed until she is engorged with blood, drops off, lays thousands of eggs and then dies! Her progeny never know of her sacrifice though – as soon as they’re born, like all good ticks, they are off searching for a blood meal. To give an idea of how much blood they suck, the Ixodes ricinus adult femaleis about 3 mm long before feeding and over a centimetre when engorged! But if that was all they did, they wouldn’t be worth mentioning, would they? No. They are vectors for (they transmit) several disease-causing germs: arboviruses, Rickettsias, Spirochetes and other bacteria. And if that wasn’t enough, their saliva contains a toxin that can cause ‘tick paralysis’ – the muscles become progressively paralysed, including those that allow breathing! Give me a mosquito any day!

Malaria

Just joking. Mosquitos love a good blood meal too, and their bites cause skin irritation. The sudden appearance of their buzzing at night just before you fall asleep can drive you crazy, if the ensuing viral encephalitis doesn’t. Not to be outdone by a silly tick, they’re vectors for a wide range of diseases including malaria. They can even transmit worms into your blood!

(left) Malaria parasites infecting a red blood cell. Unfortunately, malaria kills 400,000 to 500,000 people yearly, with children and pregnant women being especially vulnerable.

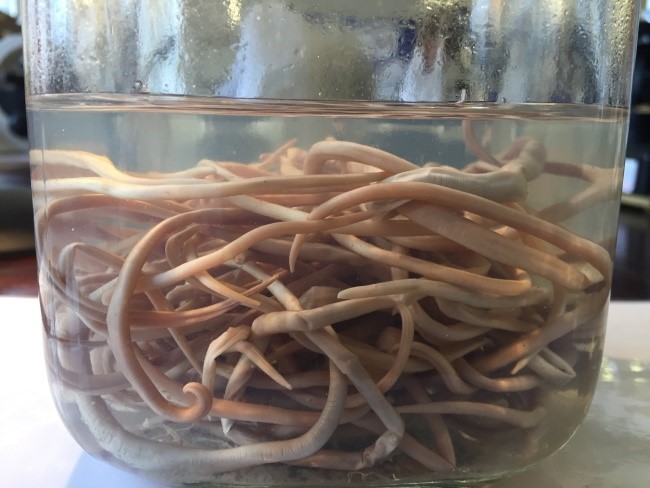

Worm Week

Worms are such clever little creatures (maybe being called one isn’t such a great insult after all). Their life cycles are often incredibly complex, starting off as eggs measured in micrometres, and some growing to over 20 metres by the end of their life (which can be for many years)!

Filarial worms, for example, are carried by flies and mosquitos. Once in the body, they grow into adults who live in the lymphatic system. These produce microfilariae, little baby worms that you can see in the blood through a microscope.

When another mosquito takes a blood meal, these babies penetrate the mosquito gut wall, migrate to the thoracic muscles and further develop as they go through 3 larval stages, before they are ready to migrate again to the mosquito’s head in time for another blood meal (and hence enter another human host). Unfortunately, they damage the lymphatic system (which normally drains away excess fluid) and give rise to “elephantiasis”, a really disabling condition where people get severe swelling in the legs and other body parts.

Needless to say, Worm Week was traumatic. But although they’re repulsive, worms are also fascinating, to the point where you can’t take your eyes off the screen when the lecturer plays a video of worms emerging from the gut during surgery. That was Ascaris, the ‘spaghetti worm’, whose egg we saw a few weeks ago. The eggs (ova) are found in several forms. The one below shows a little baby worm cuddled inside.

Larvated eggs like this one, once ingested, hatch and the larvae enter the blood stream, travel up through the liver, into the heart and lodge in the lungs. Amazingly, they spend about 2 weeks there where they mature further, then crawl up the lung to the top of the windpipe, at which point they are swallowed. When they reach the intestine, they grow into adults who release eggs and the cycle starts again.

Worm week was so traumatic that a group of students organised a revision dinner where everyone had to cook a meal based on the worm they would teach. Of course Ascaris made an appearance as spaghetti!

Some honourable mentions

Sergeant Flea. Fleas are vectors for plague (which killed a third of Europe’s population in the past), murine typhus and tapeworms.

The larva of the sheep nasal bot-fly. The female adult fly lovingly lays her eggs directly into the nose, eyes, mouth or ears of its victim.

Neglected Tropical Diseases

The worldwide burden of diseases due to Giardia or worms is enormous, but these parasites don’t receive as much attention as malaria or HIV, so they’re designated Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs). These conditions don’t always directly lead to death, but do cause significant morbidity. They often flourish in impoverished and disadvantaged communities.

The way funding is realised for global diseases is not always straightforward. Factors include publicity, political influence, national priorities, advocacy, and even perceived threat to wealthy donor nations. Yet these diseases often cause a huge amount of disability, suffering, malnutrition and childhood developmental delay – and many do cause significant numbers of deaths as well. A few years ago, it was estimated that there were half to one billion Ascaris infections worldwide and over 100 million cases of lymphatic filariasis. In an effort to address these problems, the list of NTDs was drawn and these diseases are starting to receive more attention. Like all tropical diseases, donations are what keep the humanitarian programs ticking. If you want to learn more about NTDs, visit http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/.