Ahmad Alcheikh. DTMH September 2018

Three months ago we began our studies of tropical diseases. Our journey started with public health. We travelled to different parts of the world and learned about malaria, tuberculosis and HIV. We studied worms and haemorrhagic fevers, snakes and mountain sickness, neglected and non-communicable diseases, and ended again with public health.

Ancient Illnesses

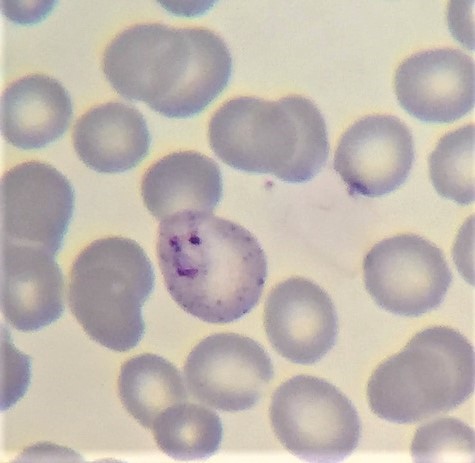

Our studies took us to places that wallow in poverty. A child is febrile, drowsy and breathing heavily in a small village in sub-Saharan Africa. Within her body, inside her red blood cells, a microscopic parasite called malaria is growing and replicating itself. Each parasite is made up of only one cell, invisible to the naked eye. Its life cycle is complex, involving the Anopheles mosquito. Scientists have found malariaparasites inside a mosquito that was trapped and preserved in the amber of an ancient tree over 20 millions of years ago – it’s a really old organism. When the parasites infect this girl’s red blood cells, they cause them to break apart, leading to severe anaemia. They also clog up the vessels in her brain making her drowsy. Unless she receives prompt treatment, the chance this child will die approaches 100%.

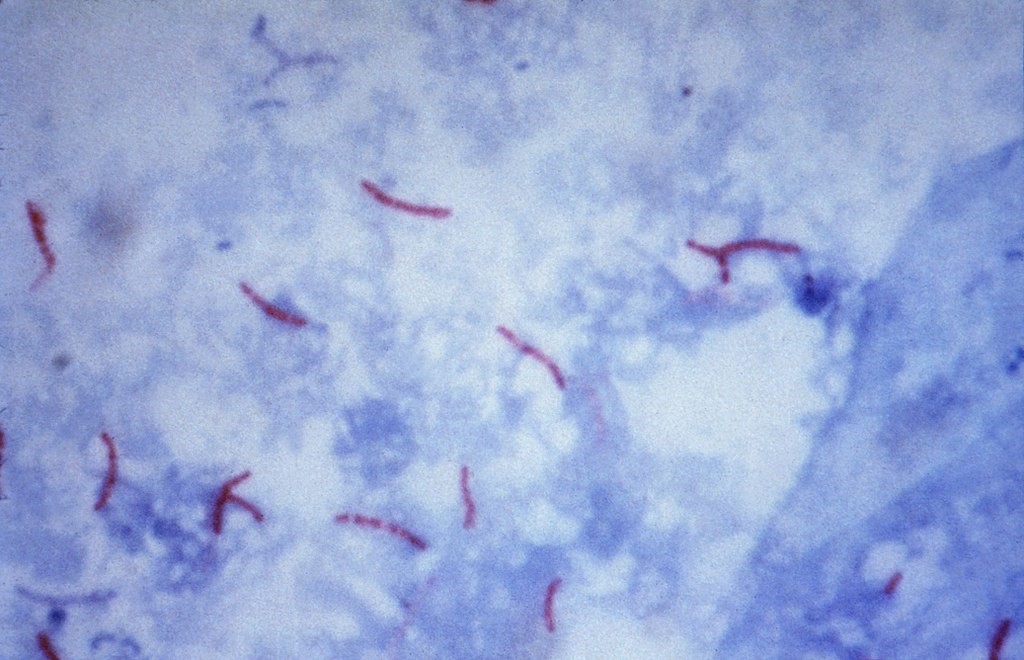

Now picture a thin man as he waits outside a tuberculosis (TB) clinic in Uzbekistan. For months, he has been losing weight and coughing phlegm streaked with blood. His lungs are riddled with an even more ‘primitive’ germ than malaria, called Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It’s a tiny rod-shaped bacterium that divides so slowly it takes weeks to culture it. Humanity has grown from the cradle with tuberculosis. There are ancient Egyptian mummies that bear the marks of TB in their spines. Millions upon millions of people have lost their lives to this disease since antiquity. Instead of the dramatic acute illness caused by many bacteria, tuberculosis slowly eats away the life of the person it infects, causing weight loss and incapacitation, and earning the name ‘consumption’. Up to a quarter of the entire world’s population is infected, but not everyone suffers from clinical disease. You might be infected today, and become ill a year or twenty years into the future. The strain of TB in this man’s lungs is resistant to standard anti-TB medication. Unless he receives highly specialised treatment, he is likely to die. One of the talks we had was about the great work one NGO has been doing in Uzbekistan in combating drug-resistant TB.

Another ancient disease that has been around for millennia is small pox. In the DTMH smallpox made only a brief appearance because, in one of the finest achievements of humankind, it’s been eradicated from the world! Smallpox probably killed over 200 million people in the 20th century. In 1959, when it was causing 2 million deaths every year, the World Health Organisation (WHO) marked smallpox for eradication. In a truly remarkable feat of science, technology, logistics and cooperation, a vaccination program was enacted that culminated, in 1980, with the WHO declaring “solemnly that the world and its peoples have won freedom from smallpox”. It’s wonderful to think that, through the efforts of WHO and many other organisations, and individuals dating back to Edward Jenner (who pioneered smallpox vaccination), many millions of human lives have been saved (possibly even our own) and countless suffering has been averted. It’s not just a question of science and programming, but also a mark of our humanity; that we could come together to rid our world, hopefully forever, of such an awful illness.

So can we eradicate malaria and tuberculosis like we did smallpox? Unfortunately, it seems unlikely, at least for the moment. Initial programs to globally eradicate malaria have since been abandoned. There are many reasons, including the biology of the parasite and its mosquito vector, lack of highly effective vaccine, cost, changing political and economic climates, and maybe even the changing actual climate (which influences malaria prevalence). Resistance of malaria and Mycobacterium tuberculosis to medications has emerged as a frightening threat to patient management as well as control on national and global scales. If the political will, research and funding to combat these diseases is not maintained, humanity risks losing the ground it has made.

Neglected Tropical Diseases

Our journey took us to the savannah regions of Nigeria where people live off subsistence farming and cattle grazing. Here, a farmer might be walking amongst the bush and stones and be bitten by a venomous snake. What happens next depends on the type of venom. If it’s a snake like the Green Mamba, a neurotoxin can cause him to stop breathing. Without prompt treatment, there is a high chance it will be fatal. But many victims live far from healthcare facilities; and many facilities don’t have appropriate antivenoms or the supportive care often required. Snakebites cause up to 100,000 deaths each year. Those who survive can be left with disabilities, scars and even amputations. Unfortunately snakebite envenomation receives little global funding and therefore makes the neglected tropical diseases (NTD) list.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs)

We also studied NCDs, because it’s not always a microbe that is causing mischief. NCDs affect impoverished people as they do all people and can have devastating effects on their lives. Imagine a teenage girl in rural Tanzania with epilepsy. Her disease is poorly controlled because of poor access to healthcare and medications, and possibly affected by beliefs regarding the cause of her epilepsy. She’s just had another seizure, except this time she falls onto the cooking fire and sustains extensive burns. Of course infections, scarring, disability and other complications can occur. But just as devastating, perhaps even more so, is the stigma attached to her changed physical appearance. In some societies, having epilepsy alone can lead to social isolation and exclusion from school and work. This fateful accident on an ordinary day might be with her for as long as she lives, and influence such things as whether she will ever marry or not.

Thinking of humanitarian work?

Here are some tips I’ve heard or read over the years.

Prepare yourself. It can take a lot of research and preparation to find a post that suits your needs. It’s good to know what you’re getting yourself into. The reality on the ground is often not as glamorous as a photograph might imply. The work can be confronting, often under less than ideal circumstances. Do some reading and contact or speak to people who are there or have recently been. Doing the DTMH is an excellent way to familiarise yourself with all aspects related to tropical medicine. You also get to meet people who have recently been on posts and can tell you what it’s like – the high and low points. It’s probably not a bad idea to undertake a short placement or two before embarking on a year-long one. Think about things you might need to bring along, familiarise yourself with the country including cultural differences, and get vaccinated early!

To care for others, you need to care for yourself! Medicine can be demanding and stressful, even in well-resourced settings. Humanitarian work also has additional physical and emotional stressors, so it’s a good idea to be physically and emotionally ready for the experience of a foreign country, dealing with dying patients, the lack of basic provisions, malnutrition, and with the social isolation some posts carry. If you don’t feel quite ready to work overseas yet but know you will want to, you can always do the DTMH now and think about doing a placement at a later time.

Find something or someone that inspires you. That way, you can not only do the work, but be passionate about it as well. It helps that humanitarian work is so broad and encompasses so many fields. In it, you’ll meet all kinds of caring people with inspiring stories. My curiosity in tropical medicine was sparked by a doctor I’d met who had done a lot of amazing work abroad and whose compassion and sense of humanity left a durable impression on me. I think a sign of being inspired is that you are left altered or changed in some way long after the experience has passed. Motivation is a complicated thing, and I think there’s no better drive to action than being inspired. And it can stay with you for life.

Think about your skills and the role you could play as part of a team. You might be surprised in the ways your skills (such a microscopy, or outbreak management) could be useful. Team work is just as important in the field as it is in city hospitals, as you might not only work with other health care workers but also traditional healers, community leaders and non-trained community workers, who are a critical part of the wider context of community healthcare and well-being.

DTMH in Liverpool

There are a few things that made doing DTMH at Liverpool feel more like fun than work. Liverpool itself is a great place. It’s one the most musical cities I’ve been to. Pick any night and it’s not hard to find great live music happening. It’s where The Beatles were born and the Liverpool Philharmonic is the oldest continuing symphony orchestras in the UK. There are always things going on in Liverpool, whether it’s arts, crafts, sports, dance, trivia, festivals – you name it. It’s also nice to walk along the waterside to enjoy the sunset. The large number of stunning heritage buildings evokes a time when Liverpool was a major port of the British empire, and where exotic diseases could be imported into the country, occasioning the need for a school of tropical medicine (the oldest in the world). Liverpool is also close to some great places you can go to for weekend trips including excellent hikes.

LSTM was a great place to study. Our teachers were fantastic and shared some amazing experiences. For me, the laboratory and clinical teaching were exceptionally well done. The course itself was quite intensive, but thankfully there were plenty of opportunities for play. You meet and become close to a great bunch of talented people, from musicians to diving instructors to former electricians-turned doctors (okay, that last one definitely shouldn’t be plural), or just genuinely nice people. Our numerous nights out or weekend trips left many fond memories, and forged friendships that I hope will last for life. It’s a relief, after a day of learning about how depressingly fatal rabies viruses are, to be able to just chill and laugh about all sorts of nonsense!

Some closing thoughts on DTMH

Perhaps the most memorable bits of the DTMH were listening to the stories of people thousands of miles away, to peek into their lives and try to share a little of their world. The photographs were my favourite part – you could almost close your eyes and be there in a hut or by the field as the sun sets on a dry African plain. There is a sense of adventure, to be sure, but compassion as well; and the photographs and individual stories brought that compassion to life, and that’s inspiring.

Doing the course makes you realise how complex our little planet is, and how many things go into determining health outcomes. We could see the human impact of poverty, policy, culture, environment, provision of clean water, sanitation and hygiene, conflict, education and health systems. There was one exercise where we were presented with stories of different people from a world of poverty, and had to brainstorm all the factors that may have contributed directly or indirectly to the health outcome described. The lists were very long.

We learned about some of the strengths and shortcomings of humanity in our struggle for good health and well-being. It’s not hard to become despondent, especially when learning about problems we’ve caused ourselves. But maybe it’s also easier to notice the pain we cause than the good we’ve achieved. There may have been more lives saved by smallpox eradication than lives lost by all the wars since 1980, but it’s not something we necessarily keep in mind. When they cause disease, mycobacteria, viruses and worms are not wilfully being malicious – they’re just jostling around in a race for survival, having been selected for this parasitic role through countless millennia. A mindless worm can’t really understand the suffering it’s causing, but the battle to rid the world’s children of worm infestations is a choice we make and feel – to show compassion to others less fortunate – and that’s a wonderful part of humanity. Of all the species we’ve caused to be extinct, there is one we can be proud of – smallpox! We’ve achieved so much, and there’s still so much more we can do.